On Monday, intake is exploding. On Tuesday, a partner says they never got the referral packet. On Wednesday, a funder report is due and the numbers don’t reconcile. By Friday, someone says, “We should fix the system,” and everyone nods, because it’s true.

Then nothing ships.

Not because people don’t care. Not because staff aren’t working hard. It’s because no one owns the decision, so the safest move is to wait, ask one more person, or keep the status fuzzy. In a justice nonprofit, that pattern isn’t just frustrating. It’s a quiet risk to clients, staff, and trust.

Key takeaways

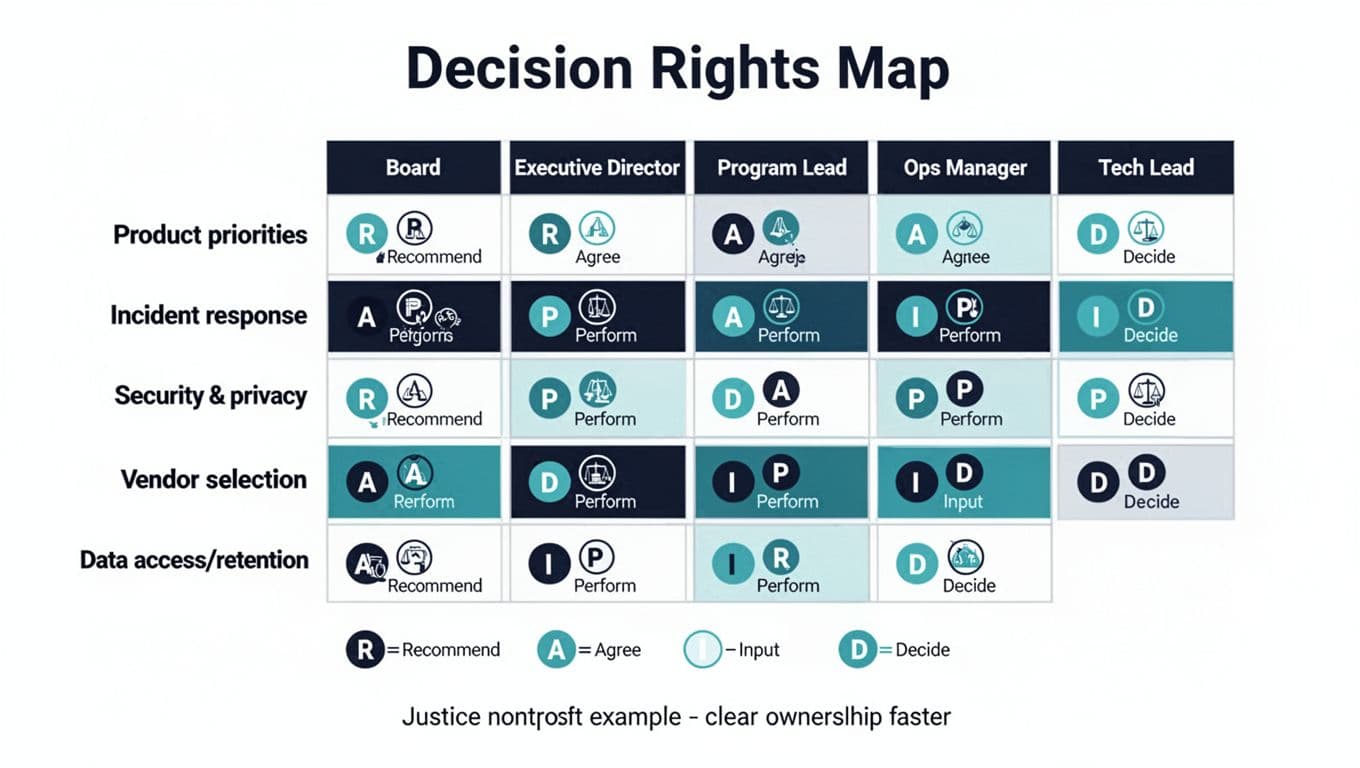

- A decision rights map turns “who decides?” from a debate into a shared, board-defensible answer.

- RAPID-style roles (Recommend, Agree, Perform, Input, Decide) reduce rework by making involvement explicit.

- An escalation ladder with time limits keeps urgent tech and ops decisions from stalling in meetings and inboxes.

- A focused 2-week workshop can produce board-approved governance without creating bureaucracy.

Why “nobody owns it” shows up most in tech and ops

Justice nonprofits often have strong mission clarity and weak operational clarity. Tech and ops sit right in the middle, so they absorb the confusion first.

Common tells:

- A vendor renewal “belongs” to three people, so it belongs to no one.

- Security decisions float, because nobody wants to be the blocker.

- Data access keeps expanding, because removing access feels politically risky.

- Projects drag, because requirements keep changing after someone new weighs in.

This isn’t a character flaw. It’s governance drift. Over time, programs grow, tools multiply, and risk increases, but decision-making stays informal. That’s how you end up living the patterns described in technology challenges for legal nonprofits, where work starts running on heroics and “sent” becomes a substitute for “done.”

If you want a useful frame for the human side of this, see Nonprofit Quarterly’s piece on mapping power and decision making. The point isn’t politics for its own sake. It’s naming reality so decisions can stick.

A practical starting move is to inventory where work falls apart end-to-end. The intake-to-outcome clarity checklist is a simple way to surface the bottlenecks that are really decision bottlenecks in disguise.

Build a decision rights map your board can approve (without slowing work)

A decision rights map is not an org chart. It’s a short list of recurring decisions, mapped to roles, with one clear decider per decision type. It replaces “let’s get everyone’s input” with “here’s how we decide, every time.”

A clean approach is to use RAPID. Bridgespan’s nonprofit-friendly overview, the RAPID decision-making tool, works well because it separates input from authority, without dismissing either.

Here’s what the map must include to be usable:

- Decision inventory: 10 to 15 decisions you keep revisiting (vendor selection, incident response, data retention, intake tooling changes, integration priorities).

- Role list: real roles, not names (Executive Director, COO/ops lead, program lead, tech lead, board chair or audit chair).

- One decider per decision: if two people can decide, nobody can.

- “Agree” is rare: limit veto roles, or you’ll recreate the same stall.

A compact example of the level of clarity you’re aiming for:

| Decision type | Decider (D) | Recommender (R) | Agree (A) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vendor renewal under threshold | Ops lead | Tech lead | CFO |

| Client data access policy | Executive Director | Privacy or security lead | Program lead |

| Major system replacement | Executive Director | Tech lead | Board committee chair |

Board approval matters because it turns the map into guardrails, not a suggestion. It also keeps the board in the right lane: oversight and risk, not day-to-day tool debates. If you want language for that balance, MIT CISR’s research note on decision rights guardrails is a helpful companion.

This map should plug into your broader plan, not float as a side document. If your org needs a simple sequence from reality-mapping to governance to execution, the technology roadmap for legal nonprofits describes a pace most teams can absorb.

Add an escalation ladder so urgent decisions don’t die in inboxes

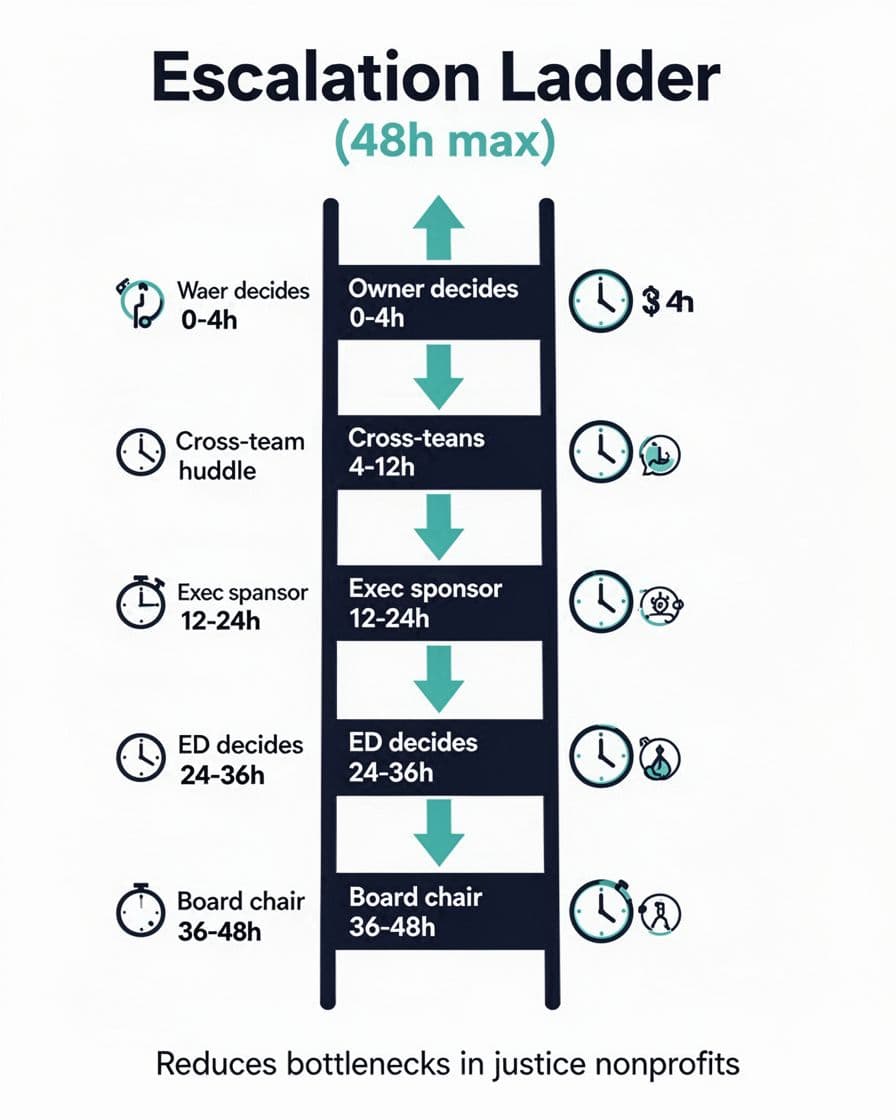

A decision rights map handles “who decides.” The escalation ladder handles “what if we can’t decide fast enough.”

Without an escalation ladder, urgency creates noise. People over-involve others “just to be safe.” Meetings multiply. The loudest voice starts steering. Then everyone feels burned, and the next decision gets even slower.

A workable ladder is time-based, not emotion-based. For tech and ops, a 48-hour maximum is often enough. The ladder can be as simple as:

- 0 to 4 hours: the named owner tries to resolve, documents options and risk.

- 4 to 12 hours: cross-functional huddle, only the roles in the decision rights map.

- 12 to 24 hours: exec sponsor decides between the remaining options.

- 24 to 36 hours: Executive Director decision, recorded and broadcast.

- 36 to 48 hours: board chair (or audit/risk chair) emergency decision, only for pre-defined categories.

Define what qualifies for escalation. Don’t leave it open-ended. Good triggers include: client harm risk, court deadline risk, material privacy or security exposure, material spend, or partner trust damage.

One “stop doing this” that creates capacity fast: stop holding meetings that end with “let’s circle back”. If a meeting is about a decision, it must end with (1) a decision, (2) a named decider with a deadline, or (3) an explicit escalation step. Anything else is just a stress multiplier.

This is also where tech and ops connect back to service delivery. If referrals and partner handoffs are a repeated pain point, the escalation ladder should include how you repair a broken handoff and who owns follow-up. “Sent” can’t be the finish line.

FAQs about building a decision rights map in a justice nonprofit

How is a decision rights map different from RACI?

RACI is often used for projects and tasks. A decision rights map focuses on recurring decisions and makes one person accountable for deciding. Many orgs mix the two, but the “D” role must stay unambiguous.

Won’t this feel top-down to program teams?

It can, if it’s done in secret. Done well, it reduces surprise and rework for programs. Program staff still provide input, but they don’t have to chase decisions across five meetings.

What does “board-approved” really mean here?

It means the board agrees to the decision categories, the deciders, and the escalation path. It does not mean the board votes on every tool choice. It’s oversight that protects the mission without pulling the board into operations.

How long does it take to implement?

The map and ladder can be drafted, tested, and approved in two weeks if you keep scope tight and use real decisions from the last 90 days as your source material.

Conclusion: ship decisions, then ship the work

A decision rights map makes ownership visible. An escalation ladder makes urgency safe. Together, they replace stalled conversations with decisions your team can carry out, and your board can stand behind.

If you want a calm starting point, book a focused conversation and bring two recent decisions that got stuck, plus one that moved fast: https://ctoinput.com/schedule-a-call. Then ask the question that cuts through the noise: which single chokepoint, if fixed, would unlock the most capacity and trust in the next quarter?