If your organization supports legal advocates, you already know the feeling: information is everywhere. Case notes in shared drives. Training rosters in spreadsheets. Partner lists in email threads. A “final” report living in five versions.

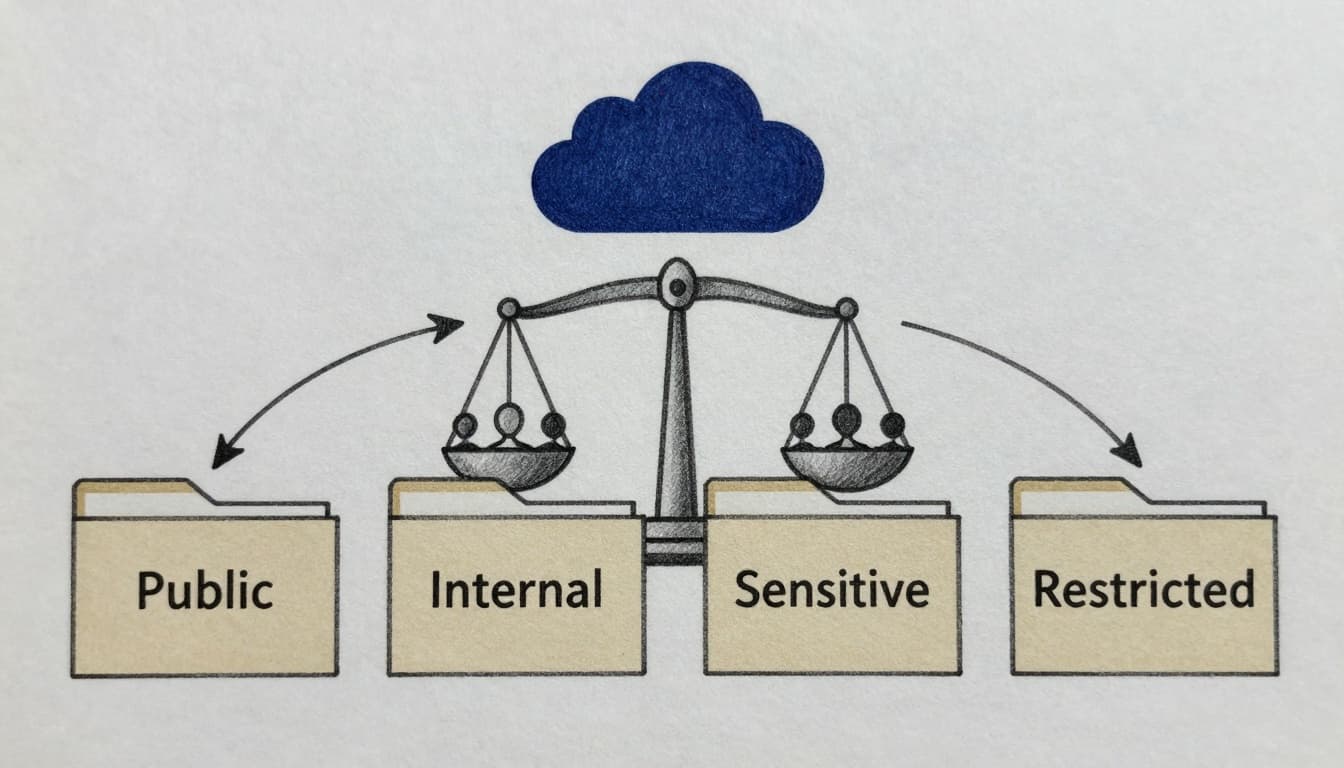

A data classification policy (which is a key part of our data classification guide for justice nonprofits) is the simple sorting system that turns that sprawl into safer, calmer work. It helps staff know what can be shared, what needs care, and what must be locked down, without turning every question into a Slack debate or a last-minute fire drill.

Key takeaways (quick and practical)

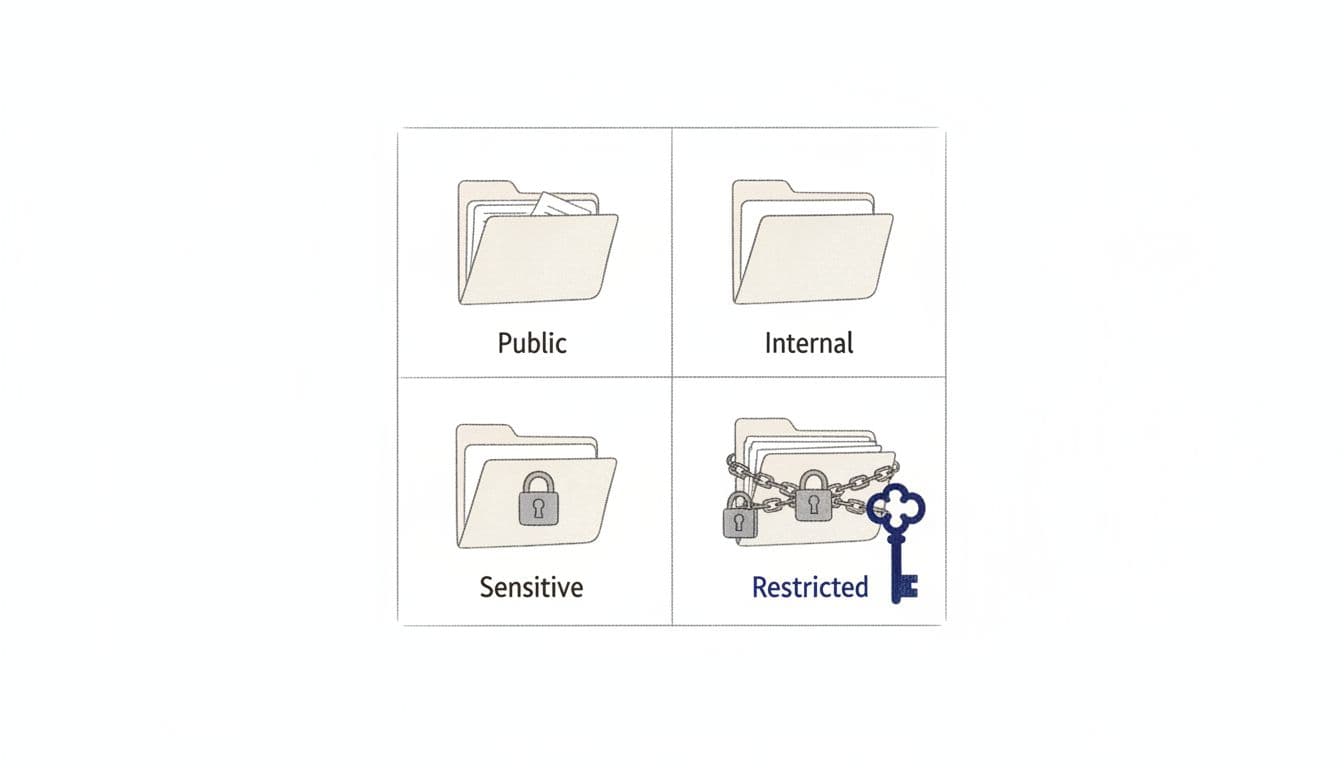

- Use four levels most teams can remember: Public, Internal, Sensitive, Restricted.

- Tie each level to handling rules people can follow in real life (where it can live, who can access it, how it can be shared).

- Start with your highest-risk data first, often client, survivor, youth, immigration, incarceration, and financial account details.

- Make it easy to do the right thing with labels, default folders, and least-privilege access, not long training decks.

- Review quarterly, because programs change, staff change, and risk shifts.

Why classification matters in justice work

In many justice nonprofits, the harm from a data mistake isn’t only reputational. It can be personal. A leaked address. A partner list shared too widely. A spreadsheet with names that ends up in the wrong inbox.

Classification also supports the less visible, day-to-day pressure:

- Board and funder reporting that pulls from multiple systems.

- Staff turnover and shared inboxes.

- Coalition work where files move across org boundaries.

- Vendor tools that store data in places you don’t fully control.

If your systems already feel fragile, this is one of the quickest ways to reduce risk without replacing everything. It also pairs well with a broader look at common technology challenges for legal nonprofits, because the same sprawl that wastes time also increases exposure.

Start small: a “good enough” data inventory

Don’t try to catalog every file. Instead, list your main data “containers” and the most common data types inside them. Think of it like sorting mail into four bins before you worry about filing cabinets.

A tight first pass usually includes:

- Cloud storage (SharePoint, Google Drive, Box)

- Email and shared inboxes

- Case management or referral tools

- CRM and donor systems

- Finance and payroll tools

- Forms (intake, training registration, surveys)

- Messaging apps and shared channels

As you list containers, add two notes: who uses it, and what would happen if it was shared by mistake. That’s enough to begin.

For a deeper, security-oriented lens on classification concepts, NIST’s discussion in Data Classification Concepts and Considerations for Improving Data Protection can help shape your thinking (even though the draft is retired, the framing is still useful).

The four-level model (Public, Internal, Sensitive, Restricted)

Here’s a practical starting point that works for many justice-focused teams.

| Level | What it means | Examples in justice nonprofits | Basic handling rule |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Safe to share widely | Published reports, job posts, public toolkits | May be shared externally without approval |

| Internal | Not for the public, low harm if leaked | Staff org chart, internal meeting notes, vendor quotes | Share only inside the org, approved tools |

| Sensitive | Could harm people or the org if exposed | Partner contact lists, complaint intakes, non-public research data | Limit access by role, avoid broad links |

| Restricted | High-risk, high-impact data | Client identifiers, protected case notes, bank details, credentials | Need-to-know only, strongest controls |

Public data: built to travel

Public data should still be accurate and version-controlled, but it doesn’t need special access barriers. One pitfall: teams often treat “public eventually” as “public now.” Drafts and pre-release findings usually belong in Internal or Sensitive until publication.

Internal data: normal operations, limited audience

Internal is where most operational work belongs. The key rule is simple: internal files shouldn’t be accessible to personal emails, volunteers without a reason, or external partners by default.

Sensitive data: protect relationships and trust

Sensitive is often where coalition work gets tricky. A partner list may not look like “client data,” but it can still expose strategy, locations, or vulnerable communities. Treat sensitive data as role-based, not curiosity-based.

If you want a concrete, readable example of how governments define and label data classes, the City and County of San Francisco Data Classification Standard is a helpful reference.

Restricted data: least-privilege, no exceptions

Restricted data is the stuff you’d never want “accidentally forwarded.” In justice work, this often includes client or community member identifiers paired with legal need, immigration status, incarceration details, safety planning, or anything tied to active matters.

A practical rule: if a document contains direct identifiers plus sensitive context, it’s usually Restricted.

Make the policy real with minimum handling rules

A data classification policy fails when it stays abstract. Staff need defaults they can follow when they’re tired and busy.

Keep your “minimum rules” short:

- Labeling: Put the classification in the file name or folder (example: “Restricted”, “Sensitive”). Consistency beats perfection.

- Storage: Choose one approved place for Restricted and Sensitive data, then actively reduce copies elsewhere.

- Sharing: Avoid public links for Sensitive or Restricted, use named access. Time-limit access when possible.

- Access: Grant access by role (program team, finance, leadership), then review access quarterly.

- Vendors: If a tool stores Restricted data, document the owner, purpose, and offboarding steps.

For teams that want a simple, non-technical framing of data categories and baseline controls, Carnegie Mellon’s Guidelines for Data Classification can be a useful model.

Common scenarios (and how to classify them)

Justice work creates edge cases. A few that come up often:

A training attendee list: Internal, unless it includes sensitive attributes (then Sensitive).

A grant report draft with program outcomes by county: Internal, but shift to Sensitive if it could reveal partner sites or small-number populations.

A referral spreadsheet with names, phone numbers, and legal needs: Restricted.

A coalition directory of direct service providers: Sensitive if it’s not public already, because it can expose who’s doing what work and where.

When in doubt, pick the higher classification, then lower it later with intention.

A rollout plan staff won’t hate

A good rollout respects attention and time.

- Week 1: Agree on definitions and examples, publish a one-page policy.

- Weeks 2 to 4: Fix the biggest risks first (Restricted data locations, sharing links, who has access).

- Weeks 5 to 8: Add light labeling, clean up shared drives, and set a quarterly review calendar.

If you want the classification work to sit inside a broader, believable plan, a technology roadmap for legal nonprofits helps connect data, systems, and risk into one story you can defend to boards and funders.

FAQs: data classification policy in real life

Who owns the data classification policy?

Usually operations or technology leads, with program and legal input. Ownership matters more than department name.

Do we need four levels, or can we do three?

Four works because it separates “Sensitive” from truly “Restricted.” That keeps people from over-locking everything.

How do we handle data shared by partners?

Classify it based on your risk, not the partner’s comfort level. Put expectations in writing for shared folders and access.

What about state data laws or public records rules?

Some justice orgs are subject to specific statutes. If you work with government data, review your obligations. Minnesota’s Chapter 13 Data Practices law shows how detailed these rules can get.

How often should we re-classify data?

Quarterly is realistic for access reviews. Full policy review annually, or when you add a new program or system.

How CTO Input can help you put this into practice

A classification policy is easiest when it’s connected to how work really happens: intake flows, partner reporting, storage habits, and tool limits. CTO Input helps justice nonprofits turn the policy into routines staff can follow, and leadership can stand behind.

That can look like:

- Building classification and access controls into your systems plan using CTO Input’s legal nonprofit technology products and services.

- Learning from legal nonprofit case studies and results that show how risk and reporting can improve together.

- Getting unstuck fast by booking a call to talk through your highest-risk data and your quickest fixes.

If you’re ready to replace guesswork with a calm, workable plan, start at https://www.ctoinput.com, then keep learning at https://blog.ctoinput.com. Protecting people includes protecting their information, and you don’t have to do it alone.